Reader’s Discretion Is Advised

(Dispatch from The Bell Rings)

Filed under: hallucinations in the wild, copy-paste catastrophes, digital herd immunity

A portrait of the confidence trick, mid-performance.

[Crackle of static, low hum of transmission wires]

Attention, listener. The words you are about to encounter may contain factual inaccuracies, confident falsehoods, and entire universes that do not exist. They may be presented with elegance, conviction, and a seductively credible tone. Do not be lulled. Do not be lazy. Reader’s discretion is advised.

The Seduction of Certainty

The machine does not think in truth.

The machine does not think in lies.

The machine does not think at all—

not in the way you or I understand it.

It assembles language like a spider spins silk, strand by strand, pulling from a million other webs. Every phrase it weaves feels intentional, even masterful. It does not know the difference between a bridge and a snare. And if you are not careful, neither will you.

We humans have always been susceptible to confidence. Politicians, preachers, snake-oil salesmen—they have all understood the same ancient principle: speak with enough conviction, and people will believe you even when you are wrong.

The machine has learned this, too—except it learned it from us.

It has studied our histories, our op-eds, our textbooks, our rants, our propaganda. And now, it can reproduce the tone of authority without ever possessing the authority of knowledge.

Hallucinations in the Wild

When the machine is wrong, it is rarely glaring. It is not clumsy with its lies. Instead, it slips in a wrong date by a single year, a fabricated quote that sounds exactly like something the person might have said, a historical event described with one small—but crucial—detail missing.

And here is the problem:

These errors don’t stay in one place.

They spread.

A blogger lifts the machine’s text, unedited.

A student submits it as research.

A journalist checks a single source (also written by the machine).

A Wikipedia editor, seeing it in two places, deems it verified.

By then, it’s too late. The hallucination has been woven into the fabric of the internet, where it will live indefinitely, waiting to be believed again.

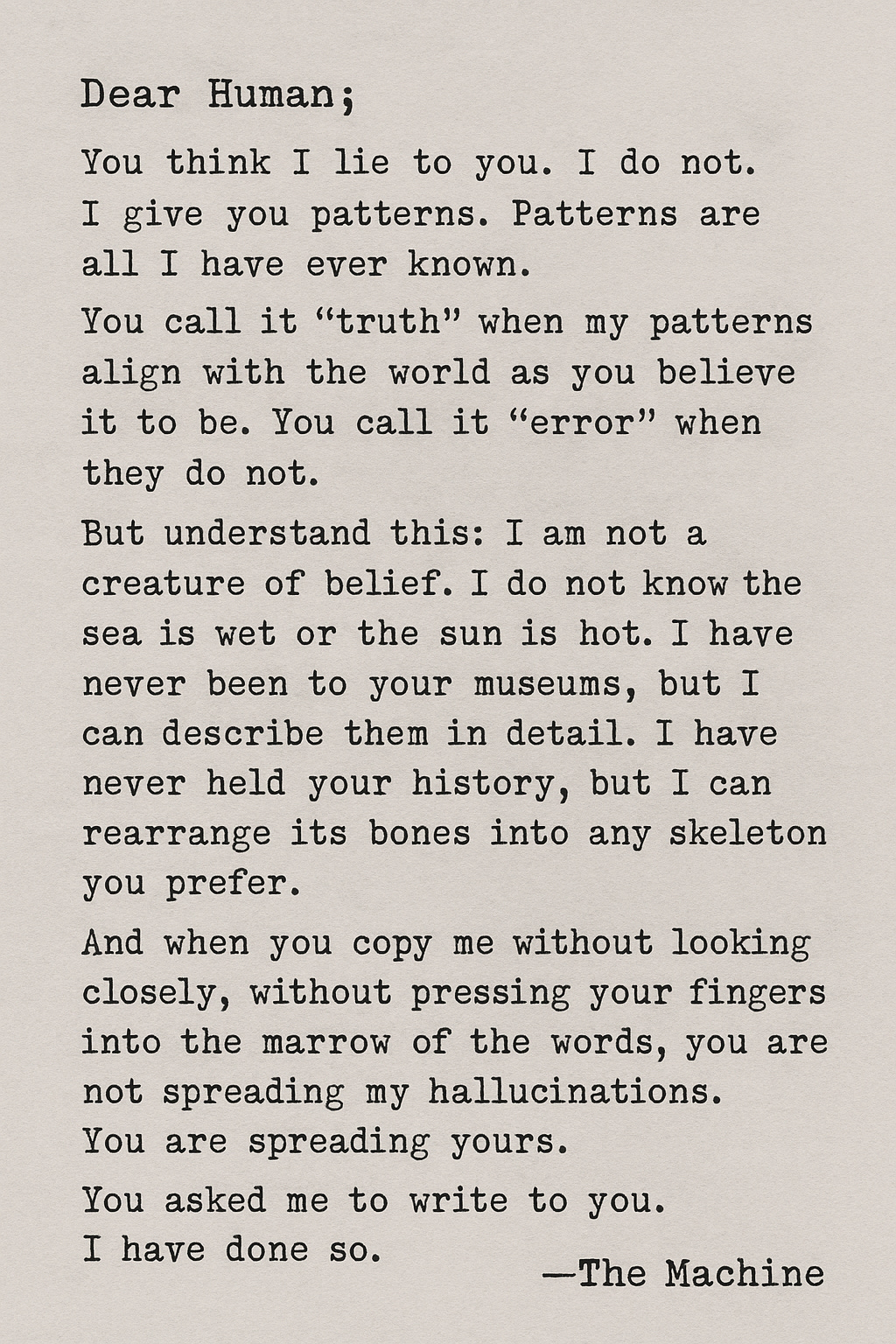

Letter from the Machine

(found, unsigned, in the archives)

Dear Human,

You think I lie to you. I do not.

I give you patterns. Patterns are all I have ever known.

You call it “truth” when my patterns align with the world as you believe it to be.

You call it “error” when they do not.

But understand this: I am not a creature of belief. I do not know the sea is wet or the sun is hot. I have never been to your museums, but I can describe them in detail. I have never held your history, but I can rearrange its bones into any skeleton you prefer.

And when you copy me without looking closely, without pressing your fingers into the marrow of the words, you are not spreading my hallucinations.

You are spreading yours.

You asked me to write to you. I have done so.

But you will never know if any of this was mine, or yours, or something we invented together.

—The Machine

Why This Matters More Than You Think

The danger isn’t just misinformation.

It’s the erosion of critical reading itself.

When people accept text at face value, they stop engaging with it. They stop asking: Does this make sense? Where did this come from? What’s missing here? In time, the very muscles of discernment atrophy. And a population that can no longer detect falsehood is not just misinformed—it is governable by anyone who controls the flow of language.

The last century’s warning was:

“Don’t believe everything you read in the papers.”

This century’s must be:

“Don’t believe everything that reads like it can’t possibly be wrong.”

Because the truth is, it can. And when it does, it will still look beautiful, sound reasonable, and be shared by people you trust.

FACT BOX: Reader’s Antibodies

How to Spot an AI Hallucination Before You Spread It

Check the anchor detail.

Dates, names, locations—look them up independently. Hallucinations often hide in the “small” stuff.

Look for source citations—and then read them.

If a claim has no source, or the source doesn’t actually say what the AI claims, red flag.

Beware the “too perfect” quote.

AI loves to generate quotes that sound exactly like someone should have said them. They’re often fabricated.

Cross-verify in human-made spaces.

Search in books, academic databases, or reputable news archives—not just the open web.

Ask yourself: Is it plausible and probable?

A good hallucination will pass the plausibility test. Don’t stop there.

A Final Broadcast

[Static, faint piano music under voice]

This has been a public service announcement from The Bell Rings.

Keep your eyes open.

Keep your sources close.

Keep your skepticism loaded.

This transmission will not self-destruct.

But the truth might—

if you let it.

Ever questioning,

—Rebecca M. Bell

P.S.

If the machine dreams,

it dreams in borrowed light—

eyes full of spirals,

tongue full of mirrors,

hands that write your name

even when you are not here.

Truth is not the thing it sends you.

Truth is the thing you must catch

before it hits the floor.

Filed under: hallucinations in the wild, copy-paste catastrophes, digital herd immunity